Understanding the Nuances of Multifamily Bond Volume Cap Recycling

By Lyla Maisto

10 min read

In an affordable housing landscape where optimism and creative solutions are more important than ever, private activity bond (PAB) volume recycling can be an attractive device for developers competing in an oversubscribed bond market. Bond volume recycling refers to a funding scheme where a bond issuer can recapture PAB volume from bond issues that are paid off early or paid down at conversion to a permanent loan phase and use that volume for another affordable residential housing project under Section 142(d) of the U.S. Code.

The laws governing PAB volume recycling are laid out in Section 146 (1) (6) of the Internal Revenue Code. Under current law, the original bond volume and recycled bond volume must have the same purpose – in our case, qualified multifamily rental housing. Thus, the volume carried forward by the issuer must be allocated to finance a new qualified residential rental housing project. As stipulated by the Code, this recycling must occur within six months of the original tax-exempt bond paydown or payoff, or the volume will expire.

In addition, the volume carried forward must also be reallocated to the new qualified multifamily residential rental housing project no later than four years after the prior tax-exempt debt was issued. As well, the tax-exempt debt on the new qualified multifamily residential rental housing project to which the carried-forward volume is reallocated must mature no later than 34 years after the original tax-exempt debt was issued.

There are two frequent uses for recycled multifamily bond volume, says Wade Norris, a bond attorney and founding partner at Norris George & Ostrow PLLC. The first is to allow large, often urban, mixed-use developments in which only 20 percent of the units are affordable at 50 percent of area median income to use tax-exempt bond financing where an oversubscribed volume allocator rations almost all new private activity bond volume to 100 percent affordable projects. The second is to enable the 100 percent affordable projects receiving only the minimum amount of volume to satisfy the 50 percent test for four percent Low Income Housing Tax Credit (soon to be a 25 percent test) to achieve the higher level of tax-exempt versus taxable debt needed to satisfy debt service coverage ratios and other underwriting criteria to generate the needed proceeds.

One recently successful deployment of the bond recycling strategy came from a joint effort by Benjamin Barker—a financial advisor and bond administrator for the California Municipal Finance Authority (CMFA)—and Norris to develop CMFA’s multifamily bond volume recycling program in 2021. In the four years since, CMFA’s program has successfully recycled bonds to reallocate funding for over 100 affordable housing projects.

Though the potential upside can be significant, the program is not without its logistical pitfalls, according to both Norris and Barker, and there are only a handful of states where recycling programs are viable. Managing the bond volume recycling process can require dedicated staff, time commitment, and flexibility.

At present, only a handful of states have recycling programs. Norris cites New York, California, Colorado, Illinois, and Washington state as success stories. He says that the common denominator among these jurisdictions is the concentration of a large portion of the multifamily PAB volume and bond issuance within just one or two agencies.

“If you look at Texas, in recent years, they have allocated over a quarter to one-third of the State’s roughly $4.1 billion in annual PAB volume to multifamily housing, but it’s spread among two state agencies and a large number of local housing authorities and other issuers,” Norris says. That decentralization, he explains, is a significant obstacle to successfully starting a bond recycling program (though it has been discussed, Norris says). “If your project is located in Texas, you can talk all you want about volume recycling, but it’s not yet really a viable option there or in a number of other states at this time.”

The “Two-Step”

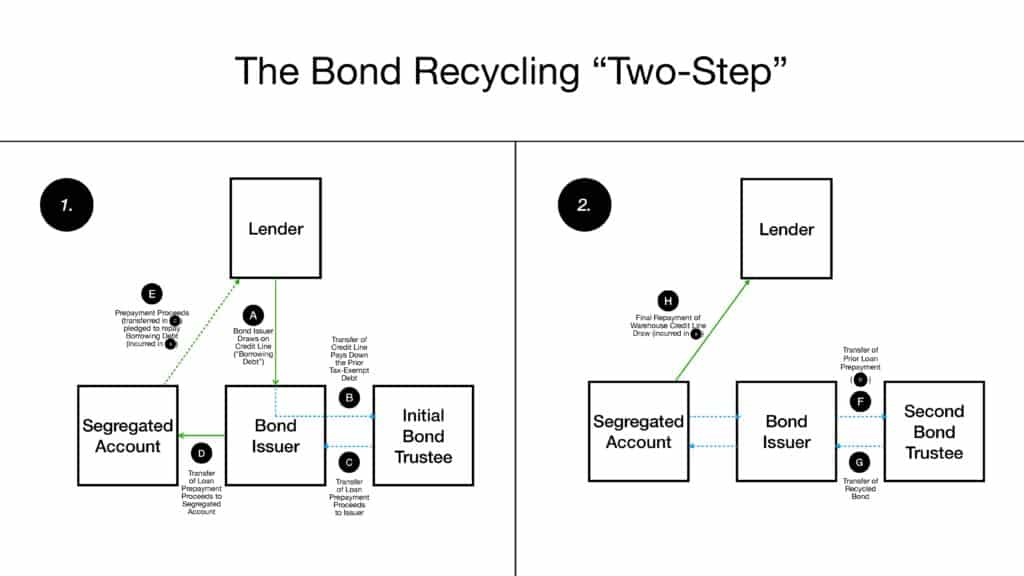

In multifamily housing projects, bond volume recycling programs involve two main steps, requiring careful coordination between lenders, borrowers, and the recycling issuer, all within tight timeframes. Prior to the first step of the recycling process, the issuer identifies a multifamily issue with an upcoming bond payoff or paydown and incurs on their books a “borrowing debt” equal to the amount of the payoff or paydown.

Thus begins the bond volume recycling “two-step.”

Step one: on the day of the payoff or paydown—and not a day before or after—the proceeds of the recycling bond issuer’s “borrowing” are used or deemed to have been used to pay off or pay down the prior tax-exempt issue. Then, the funds that would have been used to pay off or pay down the prior bond issue are transferred or deemed to be transferred to the recycling bond issuer to collateralize its line of credit or other borrowing. The prior tax-exempt debt is repaid, or deemed to have been repaid, from an alternative source.

Step two: the repayment from the initial borrower is used by or deemed to be used by the recycling issuer to make a new loan to the borrower on the second qualifying project, and the same amount of proceeds of the new tax-exempt issue are transferred or deemed to have been transferred to the recycling bond issuer to retire its credit line or other borrowing.

It is a delicately choreographed process, which Norris and Barker, as noted, fittingly describe as the “two-step,” complete here with a diagram akin to dance instructions. “When we first started looking at this in 2021, we used the following two-step flowchart to describe this process,” Barker says.

Barker stresses that recycling programs find their stride when operating at the proper scale. “We are lucky enough to have so many deals coming on, and going off, that we’re able to manage that credit facility really efficiently,” he says. “If you were doing one preservation—if you’re capturing once and then putting it to a new project—that’d be very difficult.”

Stars Align Over Certain States

Over the past three decades, as demand for affordable housing continues to skyrocket, PAB volume has become oversubscribed in many jurisdictions across the U.S. This supply squeeze has only worsened in the past decade. Between 2019 and 2020, for instance, California’s PAB allocations became volume-constrained after exhausting $900 million of carry-forward volume in a single year. Adding to the headache are the economic crises that have plagued the housing and financial sectors over the past 20 years, with accompanying shocks to credit flow, labor markets, and the supply chain leading to unpredictable cost fluctuations over the lifecycle of a project.

During the subprime mortgage crisis, in an attempt to ease some of these woes, Congress passed the Housing and Economic Recovery Act (HERA) in 2008, amending the Internal Revenue Code to authorize volume recycling programs for the first time. Agencies in New York were among the first to realize the possible benefits of these new tax regulations: soon after the HERA amendments took effect, the New York City Housing Development Corporation became the first issuer to pursue a bond recycling program, soft-launching an initiative, which, by 2012, led to the recycling of $449 million in tax-exempt PABs for developments within New York City. Meanwhile, between 2011 and 2016, the New York State Housing Finance Agency reported that it had issued over $1 billion in recycled bonds “to fund its multifamily pipeline.” Growth continued apace: in fiscal year 2023 alone, these two agencies reported a combined total of nearly $350 million in recycled tax-exempt bonds, many of which supported multifamily developments in New York City.

In New York, as with all other jurisdictions, recycled bonds cannot be used to generate four percent LIHTC. Nonetheless, Barker and Norris point to New York’s results as exemplary of the ideal conditions for a bond recycling program: a high concentration of transactions per issuer and a low concentration of issuers within the state. “Generally, a lot of the deals up there have a high debt load during the permanent loan phase; they generally require that. They give you the minimum amount you need for whatever tax credit rules you’ve satisfied. But above and beyond that, they require you to use some recycled bonds if you need additional tax-exempt leverage,” Norris says.

Barker’s California agency has realized comparable success since beginning its program in 2021. CMFA is one of two major issuers in California, and Barker estimates that the agency has completed over 100 deals that utilize recycled bonds since the program’s inception. He says that each one comes with unique hurdles related to coordination between the first and second borrower, and other parties to the respective projects. Too often, he says, last-minute schedule snags can cause ripple effects through both steps of the recycling process. “It’s been maybe once or twice that the developers using the recycled bond volume for a new project actually close on the agreed-upon closing date for the dollar amount that they said they were going to need,” Barker says. “It just moves and moves, for months sometimes, so having a credit facility and having your team in place is super important.”

Barker adds that credit facilities are not simply needed for peace of mind during a tumultuous transaction timeline but are necessary to offset the carrying costs of the recycled bonds themselves. “When recycled bonds are issued, the full amount of the new bond issued has to be issued and paid for on day one. The new bonds cannot be issued on a “draw-down” basis. And so, if bonds are used for construction, we’re giving somebody $10 million of recycled bonds that they have to take on day one, as opposed to drawing down the proceeds over time; that’s a very large interest-carrying cost. So typically, in the deal stack, you want to place your recycled bonds at the very end of your sources of financing,” he explains.

“It’s not an easy program to administer. It’s a lot of work. I didn’t anticipate it being this much work when we started off,” Barker says.

Advertisement

Certain Benefits, Uncertain Future

Echoing the sentiments of other sector stakeholders, Barker and Norris say that the recently passed provisions for LIHTC, including the 12 percent increase in the nine percent LIHTC, are a net win for affordable housing. And when it comes to bond recycling on four percent LIHTC bond-financed property, Barker says that the reduction of the PAB threshold from 50 to 25 percent is positive, because there are more PABs to spread around to other projects.

But Barker wonders what the longer-term ramifications of the reduced threshold will be for the practice of bond recycling writ large. In prior years, Barker recalls that CMFA captured about 62 percent of original obligations through recycling. With the required thresholds now reduced, there may be less excess volume cap to recycle down the line – potentially as little as 20 to 30 percent, he posits. “I’m trying to project out where we’re going to be in three years on these deals,” he says, “and I would say three years down the road we’re going to run dry. I hope I’m wrong.”

He adds that the changing PAB threshold requirements and the potential decrease in viable bond recycling down the road may simply mean a change in the type of deals being made. “It’s been lots of new construction. And I think a lot of rehab and acquisition deals will happen again, which don’t necessarily need as much bond allocation,” Barker notes.

For some, the gains realized may appear marginal. And both Norris and Barker stress—over and over again—that volume cap recycling is far from the widely available solution most people make it out to be. But in a severely oversubscribed bond market, and amid nearly unprecedented upticks in demand for affordable housing, it’s still an important tool in the kit for the jurisdictions that have been able to implement a program.

“This is not a money maker for the issuers,” Barker says, “This is a way to stretch resources and create more affordable housing.”