DOE Rebate Program Gives LIHTC Deal Incentives

By Mark Fogarty

7 min read

Developers of Low Income Housing Tax Credit projects are used to the concept of complicated capital stacks for their deals. As many as seven to ten funding sources can be found in many LIHTC deals. That may become even more complicated soon, but developers are not likely to be unhappy at the prospect of adding new Department of Energy (DOE) funding sources, residential energy rebate programs (rebate programs) under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), Sections 50121 (Home Efficiency Rebates program) and 50122 (Home Electrification and Appliance Rebates program).

Rebate programs, authorized by the IRA, could amount to a steady feature as LIHTC gap financing for developers with a taste for energy efficiency and electrification. According to Lauren Ross, multifamily building energy efficiency senior technical advisor for DOE, the maximum rebate amount for the Home Efficiency Rebates program is $8,000 per unit, meaning a 50-unit development could achieve a rebate of $400,000. For the Home Electrification and Appliance Rebates program, the per-unit cap is $14,000.

It is well suited to LIHTC deals because serving low-income residents translates to higher rebates in the DOE structure.

According to Ross, the rebates can be used with an existing building renovation LIHTC deal.

Let’s take the Home Efficiency Rebates program as an example. The program “offers up to $8,000 per unit for low-income housing for whole-home energy efficiency,” she says. But in some cases, the amount can be higher.

“The state can choose to go higher for buildings that serve low-income households,” she adds.

“The Home Efficiency Rebates program is based on modeled or measured energy savings,” says Ross, and since it is administered by state energy offices (SEOs), details can vary from state to state.

The way the rebate is determined, the multifamily building owner or individual householder “conducts a home energy assessment, then the auditor will come up with a whole energy retrofit and model the savings upfront so the owner can get a rebate when the work is completed.”

There is another way the rebate can happen as well. “They can choose to go down a measured savings pathway, and in that case, they would baseline their energy savings, develop a project scope with a contractor and a year after completion look at utility bills, see what level of savings they achieve, and if they hit a target, they get a rebate.”

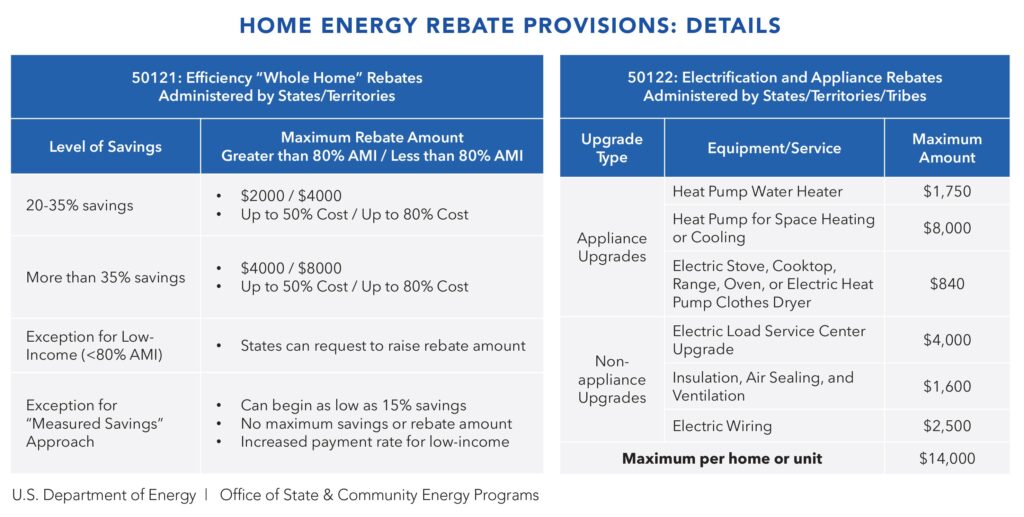

There are various energy savings levels to be achieved to get the rebates. In a presentation at National Housing & Rehabilitation Association’s 2024 Annual Meeting, Ross shared a slide showing that the rebate amount could come to 50 percent of energy rehab costs for those above 80 percent of area median incomes (AMI) and 80 percent for those below 80 percent AMI, with the caveat that states can offer even higher rebates for households below 80 percent AMI.

If a 20 to 35 percent energy savings is achieved, maximum rebates are $2,000 for those above 80 percent AMI and $4,000 below 80 percent AMI.

If the energy savings are above 35 percent, those maximums increase to $4,000 and $8,000.

States, though, can request to raise the amount for low-income residents.

The minimum savings level is lower for the second possibility, the “measured savings” option. That starts at 15 percent savings and there’s no maximum rebate.

States must allocate at least ten percent of their rebate funding to serve low-income multifamily buildings.

There’s a lot of money in the Home Efficiency Rebates program, a total of nearly $4.2 billion going to states. State allocations vary from a high of $292 million for California to a low of just under $25 million for the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.

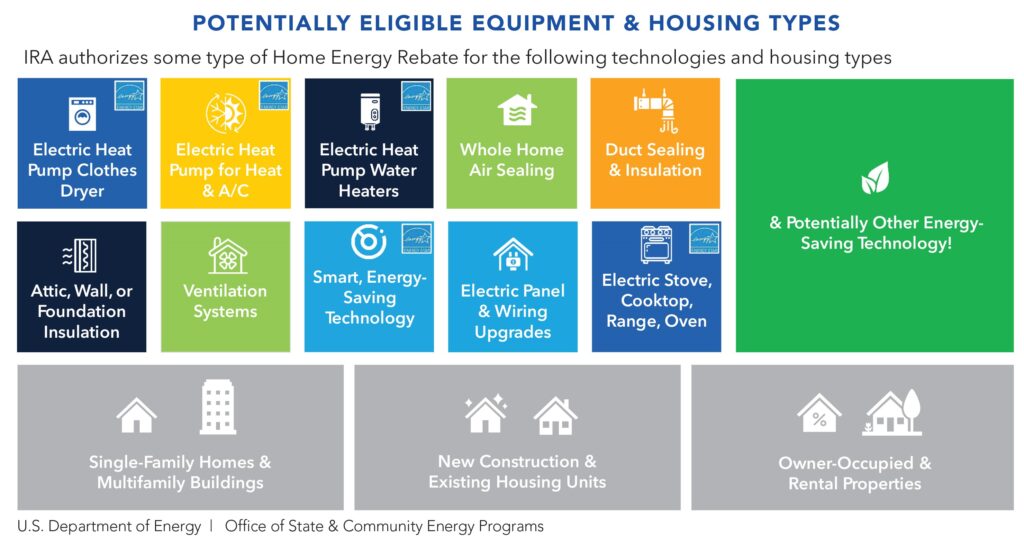

Importantly, the types of allowable retrofits do not include solar. Eligible measures according to the slide presentation are items such as whole-home air sealing and ventilation systems.

Ross notes that the states must apply to DOE for funding. “Once a state gets their funding and launches their program, developers can start scoping their projects and applying for rebates.”

States need to apply for the program by January 2025.

Some states will begin launching programs starting this spring.

DOE does not provide tax guidance, so Ross says developers should talk to their lawyers and accountants about possible impacts on eligible basis and whether the rebates are counted as income. “Those aren’t rules DOE puts forward.”

Ross also presented a White Paper at NH&RA’s meeting that addressed the basis and tax issues, while making the following points:

- The Home Efficiency Rebates program is only for existing buildings and cannot be used for new construction.

- Depending on the financing requirements of the project, building owners will have to assess the feasibility of receiving a rebate through the modeled or measured savings pathways. For instance, a requirement of the measured pathway is a calculation of actual energy savings no less than nine months after the final installation.

- Because grants may reduce eligible basis, LIHTC developers/sponsors frequently convert grant funds into loans when invested into their project financing. However, DOE does not permit Home Efficiency Rebates funds to be invested as loans. Instead, there is flexibility in how the eligible rebate recipient elects to invest equivalent funds from other available sources into the LIHTC structure (e.g., a member of the partnership receives the rebate and then loans that amount to the partnership).

- The applicant (i.e., eligible recipient of a rebate) for the Home Efficiency Rebates could be the building owner (including members of the tax credit partnership), an aggregator or an energy efficiency implementor who could float the cost of the improvements and provide the discount upfront.

- In the Home Efficiency Rebates program, a state may provide a rebate reservation system for eligible rebate recipients applying with the modeled pathway before construction.

- Although DOE does not allow State Energy Offices or their subgrantees to loan the rebate funds to projects, SEOs may wish to coordinate closely with state housing agencies to align the Home Efficiency Rebates so that they can work effectively for low- and moderate-income multifamily project finance.

- There is a requirement for states to perform quality control on a sample of completed projects as part of the consumer protection plan. Projects flagged due to quality issues would most likely result in the State Energy Office being required to make administrative changes to ensure higher quality assurance standards are maintained moving forward.

The bottom line on the rebates? “It’s a great resource for building owners looking for gap financing to do energy efficiency upgrades to make their buildings healthier and more affordable,” says Ross.

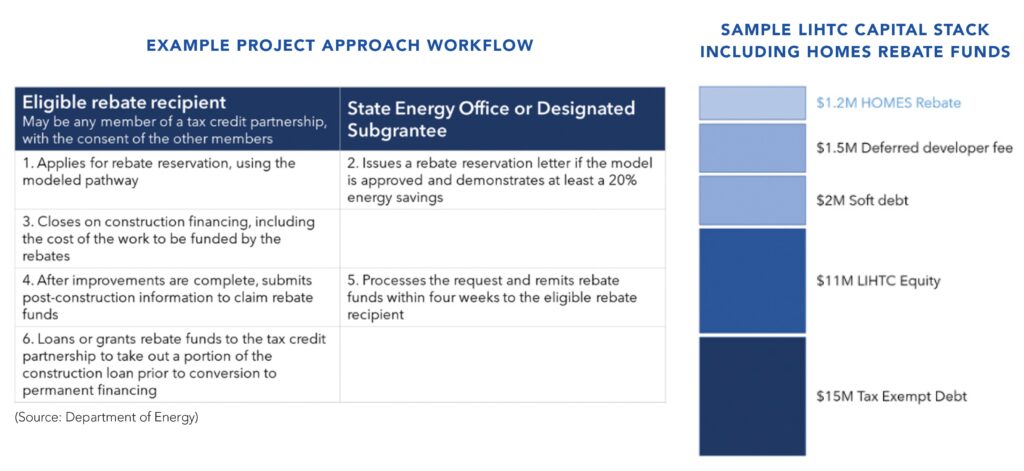

An Example of

How the Rebates Might Work

In the examples shown below, a project receives a LIHTC allocation to preserve affordability and renovate an existing building. The renovation will provide a range of upgrades and repairs, including energy efficiency upgrades that may be eligible for Home Efficiency Rebates.

The developer has identified an eligible scope of work for the project that maximizes the potential rebate amount of $8,000 per unit based on the modeled energy savings achieved. A member of the project’s ownership entity applies to the State Energy Office for a rebate reservation using the modeled pathway, before closing on its construction financing.

The project includes the costs of the investments, which will generate the rebate in the construction financing. The repayment of the construction loan will then rely on both the permanent financing and the Home Efficiency Rebate proceeds.

After construction is complete, the rebate recipient applies to the State Energy Office for its rebate, and the State Energy Office funds the rebate within four weeks. The eligible rebate recipient then redeems the rebate post-construction and uses it as a take-out source for the construction loan.